O site The Nature of Cities promove mensalmente mesas redondas virtuais a partir de um tema previamente determinado. Neste mês de janeiro/2015 os participantes responderam à seguinte questão:

GLOBAL ROUNDTABLE

Urban water fronts have typically been sites of heavy development and often are sites of pollution or exclusive access. But they have enormous potential benefits. How can we unlock these benefits for everyone? Are there ecological vs. social vs. economic tradeoffs?

O texto reproduzido abaixo – contribuição do blog Urbe CaRioca para as discussões propostas pelo The Nature of Cities que em breve publicaremos aqui em português – integra um conjunto de quinze artigos a respeito de cidades e suas frentes d’água publicados no referido site no último dia 06/01. Comentários nos artigos serão muito benvindos. Para acessar todos os textos clique AQUI.

Aproveitamos para agradecer a David Maddox pela oportunidade de participar desse importante fórum de discussões, e a Cecília Herzog pela indicação.

Andréa Redondo / Urbe CaRioca

.jpg) |

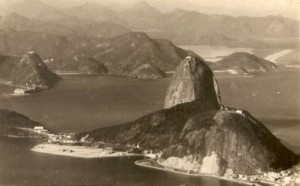

| Sugar Loaf and Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, 2012 Photo: Camila A. G. R. |

O RIO DE JANEIRO À BEIRA D’ÀGUA

Andréa Albuquerque G. Redondo

Rio de Janeiro was founded 450 years ago, grew around Guanabara Bay and several hills, and spread into North and West directions towards inland. From the 19th Century on it headed South along the coast. Our ‘East’ is the sea. Natural and urban environment in Rio exist together.

The waterfront is heavily populated. In the northern part of the bay port and industrial activities once closed down created abandoned areas, as occurred in many cities. In the front shore neighborhoods, habitation, commerce and services sector are mixed, except at the front land, destined to be apartments, hotels and restaurants by the land-use policy.

Unfortunately water pollution is a problem. Cleaning the marvelous Bay is always postponed, beaches are polluted, lagoons and streams are silt. The absence of sanitation in some vicinities and inefficient controls even in official sections brings bad results from an ecological standpoint. Fortunately, Brazilian Law prohibits exclusive access to the shore, as beachfronts are federal property, except in military areas. It is said that beaches are considered the most democratic space in Rio!

Irregular constructions, or ‘favelas’, exist all over the city. The consolidated ones are popular neighborhoods. Housing policy in early 60’s and 70’s removed some from the acquisitive South area, and transferred residents to distant projects. Those at Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon were replaced by very high value buildings. In North and West regions favelas still go around lagoons, canals and streams.

Recover the degraded environment or urban land vs. social issues is a complex task. Sometimes radical actions are required to defend either (1) ecology or (2) people. In the first case is necessary to prevent predatory urban occupation—formal or not—“rescue” invaded shorelines, and free ecological protected areas, even if families must be transferred according to the 1990’s Housing Policy. Second, if removal of constructions is impossible due to its consolidation and extension, adequate planning may reduce harm and with ecological benefits for all.

In both conditions land value grows. Avoiding gentrification process caused by “market laws” is a challenge, especially in Rio where pressure from real estate business is strong and permanent. It’s a public sector duty (1) in areas where construction is proper, to stimulate multipurpose structure for habitation, commerce and services, provide public spaces; and (2) in protected areas search private sector support to sustain it or assume the necessary budget.

.jpg) |

| Sunset at Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro Photo: Camila A. G. R. |

Successful stories depend on the way we look. At Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Rio’s post-card, there was a trade-off. For landscape, tourism, investors and new residents, it’s a success story. However, new projects create new places of poverty, with lack of infrastructure, to which poor people, losing their original homes, are moved. The transference model has been destructive and inappropriate.

The Port Region renovation is still unpredictable. Planning was conducted by financial interests and allows the construction of 30-50 floor towers. This area received huge and expensive infrastructure and has attracted only entrepreneurs and investors for commercial buildings construction. Without permanent residents it will be another lifeless place.

Protection for natural and urban environments must be appropriate and guide city planning whenever necessary for ecological purposes, independently of the land’s economic value, though balance is required.

|

| Stone extration in XIX’s and early XX’s in Urca neighborhood, near Sugar Loaf |

Respect for environmental questions should be imposed by building codes and law enforcement. However, in the name of the 2016 Olympics, occupation has increased in free areas, flood-risky grounds and fragile hillsides, propelled by questionable new urban ratios for higher and bigger buildings and hotels, plus fiscal incentives. Pressure for real estate private enterprises along shorelines (and everywhere!) has had governmental support. Recent examples are a luxurious hotel and condo, and the polemical Olympic Golf Course built in Marapendi Reserve, both in protected areas, and worse, the course eliminates an ecological park, and suppressed potential avenues of dissent, despite lively defenders, urban planners and lawyers protests.

200 years agoRio grew turning back to the water; sea bathing was a medication. 100 years ago demolished historic hills gave place to densely occupied flat ground and provided landfill over waters; stone mountains were raw material for construction, pavement and wharfs. There were positive actions in past, too: in the Imperial 19th Century Tijuca Forest, devastated by coffee crops, was replanted; in the 20th Century the municipality prohibited stone extraction; Culture and Environment Preservation policies were reinforced. Avoiding regression is imperative.

Without its Nature Rio would not be an Historic Urban Landscape. Even in our difficult current situation, Rio de Janeiro is still the Wonderful City!

_________________

About the Writer:

Andréa Albuquerque G. Redondo is an architect devoted to the study and analysis of building codes and urban laws especially related to Rio de Janeiro, and its consequences for the City development.